brh/tl/kbDuring his first two years working at a large oil field in Kazakhstan in the early 1990s, Joel Haight saw eight people die on the job.

It was a vast operation run by Chevron Corp. in partnership with the government, and Mr. Haight was the project’s safety director. The oil wells and processing plants were run by Kazakh workers, Russian supervisors and Turkish maintenance crews.

Some of the technology and job requirements were unfamiliar, and cultural tensions wedged themselves into work. The first time there was an accident, workers rounded up the culprit and prepared to beat him up as punishment.

Mr. Haight had long had an interest in human factors engineering — which includes designing machines and processes to match the humans who would be carrying them out. This assignment gave him a perfect chance to mind the humans involved in designing a safety program.

"Safety is very much a human-centered process," he said. "Human factors engineering seeks to optimize and match up attributes of humans with the expectations of a job. When those are not properly matched up, people are more likely to get injured."

Human factors research dates back to the early 1900s but only recently has become a trending topic in safety.

"Designers, engineers, researchers and practitioners need to understand the human as a component in the system — and as one that is interactive, variable and adaptable," Mr. Haight wrote in an article pushed in Professional Safety, a journal of the American Society of Safety Engineers, in 2007.

The discipline will be a central component of a new safety engineering certificate program at the University of Pittsburgh, where Mr. Haight now teaches.

The program is expected to launch in the fall and will be available to Pitt graduate students, as well as industry professionals. Mr. Haight and the university are hoping the latter group will show up en masse. The program’s advisory committee is stacked with heavy hitters from the oil and gas industry, including Chevron, BP and several large insurance companies.

Human factors engineering isn’t necessarily intuitive to oil and gas companies, which use success metrics that tend to focus on production, productivity and growth.

“Industry is still trying out that human performance thing,” said John Cornwell, Chevron’s regional health, environment and safety manager who helped shape Pitt’s new program.

“No 'they'”

In Mr. Cornwell’s office at Chevron’s Appalachian headquarters in Moon hangs a framed sign of the word “they” with a red slash through it.

It’s a way of removing blame from an accident investigation to get at the root cause. If human error prompted the accident, the idea is to find out what preceded that human error and what motivated it.

"When it comes to human behavior, organizations are perfect systems," said David Uhl, senior vice president and partner at Aubrey Daniels International., an Atlanta management consulting firm. "People do what they do because it’s working for them. If we have folks taking short cuts, there’s something in that system that’s perpetuating it.

"Lots of people say safety is number one," Mr. Uhl said. "But in day-to-day practice, if the first thing my boss asks me is how are we doing on the schedule, how’s my productivity," that sends a message about priorities.

For the past year, Aubrey Daniels has been working with Consol Energy Inc. on beefing up the Cecil company’s understanding of how human factors play into its safety performance.

“It’s easy to fall back on, ‘they made the wrong decision,’” said Lou Barletta, Consol’s vice president of safety.

But the company was interested in what it could do to promote good decisions. There’s a lot of money riding on it.

Consol has spent more than $1 billion on safety and compliance over the six years. After years of improving its safety stats, Consol slipped in 2013. Its recordable incident rate rose by 32 percent from 2012, while lost workday incidents increased by nearly 50 percent.

“The emphasis this year to make sure there's not a ‘just check the box’ mentality. What we have to do — and we're changing our culture — we have to recognize positive performance. And the more we recognize it, that will become its own habit, take its own legs and run with it,” Mr. Barletta said.

Consol is shooting for a 4-1 positive vs. negative feedback ratio. It’s looking to ask more than tell and to get employees talking about their safety processes rather than just following instructions.

“We’re touching in a new area, somewhat uncomfortable for our culture,” Mr. Barletta admitted.

Oil and gas

Consol has two sides of the house, each with different safety challenges.

The coal side is staffed by company employees, many of whom are third- or fourth-generation coal miners.

"On the gas side, you’ve got third parties and different operators that have different standards and different expectations," Mr. Uhl said.

The perk of having this kind of tiered project structure — where an operator hires contractors who hire subcontractors — is that the main operator can impose its safety values on everyone down the food chain. That's done both by contract and by a trickle-down cultural influence on the work site.

In interviews with Consol's contractors, Mr. Uhl found even those who gripe about extra safety requirements tend to transfer those practices to their work for other companies.

Mr. Barletta said he’s started to see contractors, even small ones, doing risk assessments, which they call JSAas, or job safety analyses.

Nick Kuntz, vice president of risk control with Downtown-based HDH Group, said he’s been advising clients to conduct cultural surveys of their employees for the past several years, which, in the case of safety, often end up as “come-to-Jesus” moments for management.

Mr. Kuntz may ask executives, supervisors and laborers to rate how important they feel safety is in the company's eyes. Top-level managers always put it in the top three, he said.

“For middle management, it’s typically not as important. People in the field might say, this is number 20 on my list. I’d love for it to be 3 or 4, but it’s not.”

Partly, that is because safety isn't quantified the same way as production goals. It's hard to measure. It's a lagging indicator.

“Your production numbers are hard numbers,” he said. “Safety is more a pie-in-the-sky thing. Often times for companies, production numbers aren’t a surprise. But safety is," and it shouldn't be.

The rate of serious accidents in the oil and gas industry has decreased dramatically since Casey Davis, vice president of health, safety and environment with Texas-based Wild Well Control, a company that responds to serious oil and gas accidents like fires and blowouts, entered the field 33 years ago.

But human behavior tends to be a constant.

Analyzing 69 incidents that his company has responded to over the past six years, Mr. Davis found 92 percent were the result of human error and most of those were caused by “lack of formalized training.”

“The activity that was assigned to them, they were not fully familiar with,” he said.

That’s been a concern in quickly developing shale plays where many new workers are entering the field.

But Mr. Davis said he finds the same is true in old oil and gas fields.

“We see it even in areas that are not shale plays,” he said. “There’s no differentiation that we see between the severity or probability of these incidents from a mature field or a conventional one.”

Human vs. machine

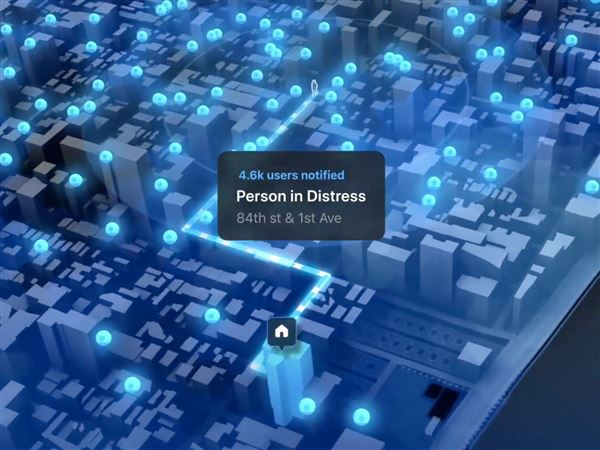

With humans prone to error and judgment-clouding events — plus being pretty expensive to have around — many industries have leaned on machines to increase safety.

There’s a lot of appeal to automating, especially in oil and gas. Instead of having an enclosed single facility to monitor, there are hundreds and thousands of points to keep track of — pipeline taps, well heads, compressor stations, condensate tanks.

Mr. Haight, however, is cautious about engineering humans out of the equation.

Human interaction with a machine is mostly influenced by how much he/she trusts that machine, he said. Too much trust could cause the operator to defer to the machine too much. It could make the human complacent, rusty, over reliant, and helpless in an emergency. Too little trust — if a system doesn't perform reliably, for example — can cause workers to ignore a machine’s legitimate warnings.

Mr. Haight has been researching the right balance between automatic and human controls. He recently submitted a grant proposal to the U.S. Department of Energy to study how nuclear reactor operators perform at different levels of control over the process.

In an experiment, he plans to plant licensed nuclear operators in a simulated control room, hook them up to electrodes, and vary the level of automation and their level of engagement. Then he’ll measure their error rate under different conditions and track what happens physiologically at each step.

Everyday, workers switch between "active thinking" and "habits of mind" several times, he said. The more they are engaged, the more they tend to stay in "active thinking" mode which is better for safety, according to Mr. Haight. But what makes them switch between the two isn't well understood.

The nuclear industry is primed for this kind of research.

At its headquarters in Cranberry, Westinghouse Electric Co. has a control room simulator, identical to the control room inside an AP1000 nuclear reactor, where licensed operators train.

As the nuclear industry moves from analog control rooms to digital ones, human considerations like lighting, temperature, even ergonomics, play a part in the design. When Westinghouse was designing a control room for a South Korean company, for example, it lowered the height of its desks to account for shorter operators.

"Anytime we do anything with a control system at a plant, we have human factors in mind," said David Howell, senior vice president of automation and field services at Westinghouse.

Human factors considerations are part of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s assessment of nuclear plant design and the licensing of its operators.

The AP1000 control looks much different from the cortex of an active Westinghouse reactor in the U.S. where operators must pace a long wall of screens checking indicators. Digital control rooms display all that information on a few computer screens. Operators can sit and with the click of a mouse, access any indicator they need to make a decision.

This give them more control to do bigger picture analysis, Mr. Howell said.

Mr. Haight said he hopes to test if the new model fosters more or less “active thinking.”

Anya Litvak: alitvak@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1455

First Published: May 6, 2014, 12:05 p.m.