Less than three months before he set foot on the moon, Neil Armstrong wrote a letter to a teenager in Point Breeze.

Mike Suley, 69, still has it. Or he did. He’s loaned it to the Heinz History Center for its “Destination Moon” exhibit set to open Sept. 29.

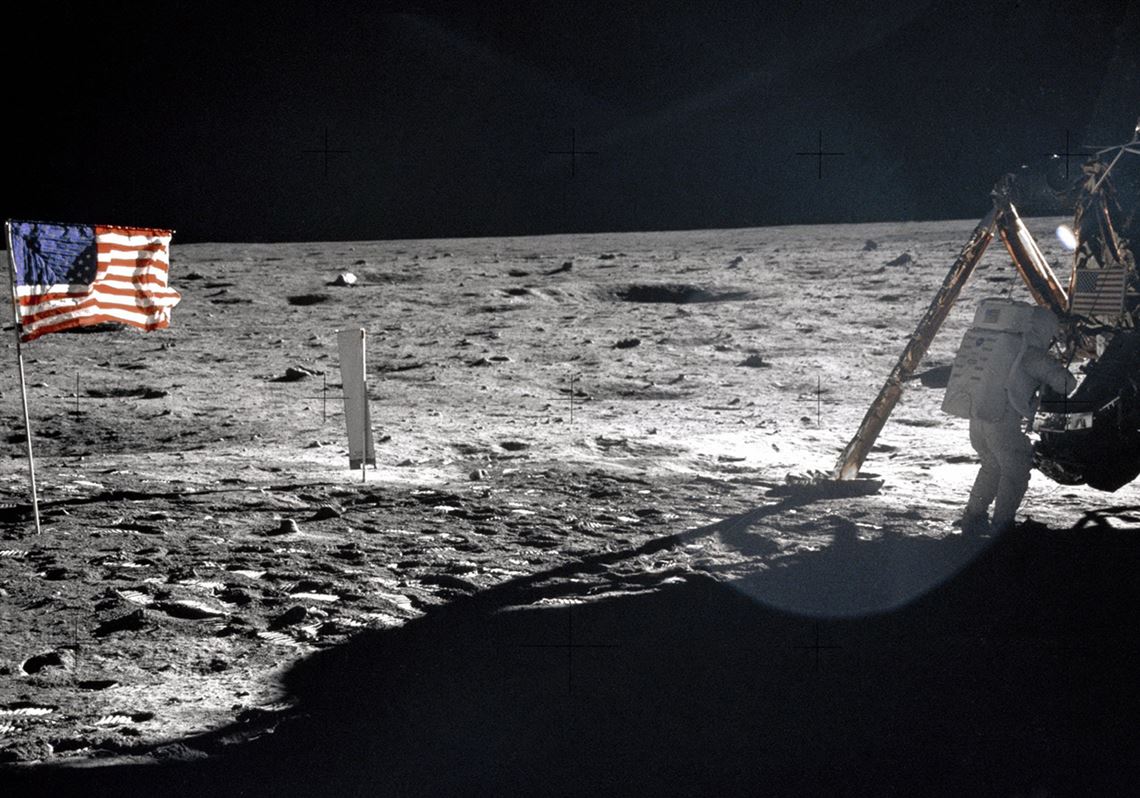

The command module Columbia, the part of the Apollo 11 spacecraft that returned the astronauts to Earth, will also be on display. But the little note from the astronaut is suddenly topical because it has to do with the American flag he’d plant on the lunar surface July 20, 1969.

It seems the latest red-and-white-and-blue boo-boo on some Americans’ fragile patriotic psyche is a new movie, “First Man,” that doesn’t show the moment that Mr. Armstrong and fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin planted the American flag.

That the movie won’t even be in theaters until Oct. 12 doesn’t mean people can’t get a head start being appalled. The national pastime these days seems to be searching out ways to declare oneself offended. Conservatives and liberals both play this game, and stalwarts on the right predictably staged a public whining the moment they encountered reports of an inadequate display of flag waving. Or, in this lunar landing, flag hanging.

Mr. Armstrong’s two sons and the author of his biography since have suggested everyone chill out and wait for the movie. I’ve seen the trailer and it’s crystal clear those were Americans getting us to, and landing on, the big white orb in the night sky.

The social media flareup amounts to an ad for the “Destination Moon” exhibit and so Mr. Suley doesn’t mind it. We talked about why he wrote Mr. Armstrong early in 1969.

Back then, there were rumors the astronauts were going to plant a United Nations flag on the moon. Mr. Suley, then 19, didn’t like that much. Americans were paying for the trip; Americans were risking their necks to get to the moon; and “this would decisively end the space race with the Soviet Union.”

He didn’t make a copy of his handwritten letter to Armstrong. But he remembers asking that the astronaut use his influence to get the American flag on the moon. He shared a photocopy of Mr. Armstrong’s April 28, 1969, reply on National Aeronautics and Space Administration stationery:

“Dear Mr. Suley:

“Thank you very much for your kind note. I appreciate your recommendations and do, in fact, agree with them in general. A high level NASA committee is in the process of considering the symbolic activity to take place on the lunar surface and rest assured your feelings will be considered. I think you will be pleased with the final outcome.

“Best regards.

“Sincerely,

“Neil A. Armstrong

“NASA Astronaut”

Mr. Suley put that letter atop his TV set the night his favorite astronaut made “one giant leap for mankind.” And 15 years ago, Mr. Suley shared that note with James R. Hansen, then writing the biography, “First Man,” on which the movie is based. Mr. Hansen is also co-producer of the film. (He will speak and sign his book at the History Center at 7 p.m. Nov. 1. Tickets start at $15.)

In an email, Mr. Hansen said one film reviewer counted the American flag showing up 1,000 times in “First Man,” a movie chock full of scenes of American life in the 1960s. “It’s just a reflection of our time that these things become politicized,” he said. “I encourage everyone to go see the movie and judge for themselves.”

The flag-raising was only symbolic; the U.S. was a signatory to the United Nations Treaty on Outer Space, and that precluded any territorial claim. In President Richard M. Nixon’s inaugural address in January 1969, he said, “As we explore the reaches of space, let us go to the new worlds together — not as new worlds to be conquered, but as a new adventure to be shared.”

That didn’t mean we couldn’t declare who got there first, of course. Congress barred NASA from placing the flags of other nations, or of international associations, on the moon during missions funded solely by the U.S.

Mr. Armstrong’s sons, Rick and Mark, noted that “the filmmakers chose to focus on Neil looking back at the Earth . . . Of course, it celebrates an American achievement. It also celebrates an achievement ‘for all mankind’ as it says on the plaque Neil and Buzz left on the moon.”

By the way, Jack Kinzler, a graduate of the old South Hills High School on Mount Washington, was the NASA man who designed the flag assembly with a horizontal crossbar to offer the illusion of a flag flying in the breeze. A prototype of Mr. Kinzler’s device is also part of “Destination Moon.”

Brian O’Neill: boneill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1947 or Twitter @brotheroneill

First Published: September 16, 2018, 4:00 a.m.