Think the battle over U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh was as shocking as confirmation struggles get, with highly partisan allegations of sexual assault?

Guess again.

In another late summer nearly a century ago, Paul Block, then the publisher of the Post-Gazette and the Toledo Blade, gave one of his best reporters a tip about another Supreme Court nomination. That tip produced a ripping scandal — and a story that won a Pulitzer Prize.

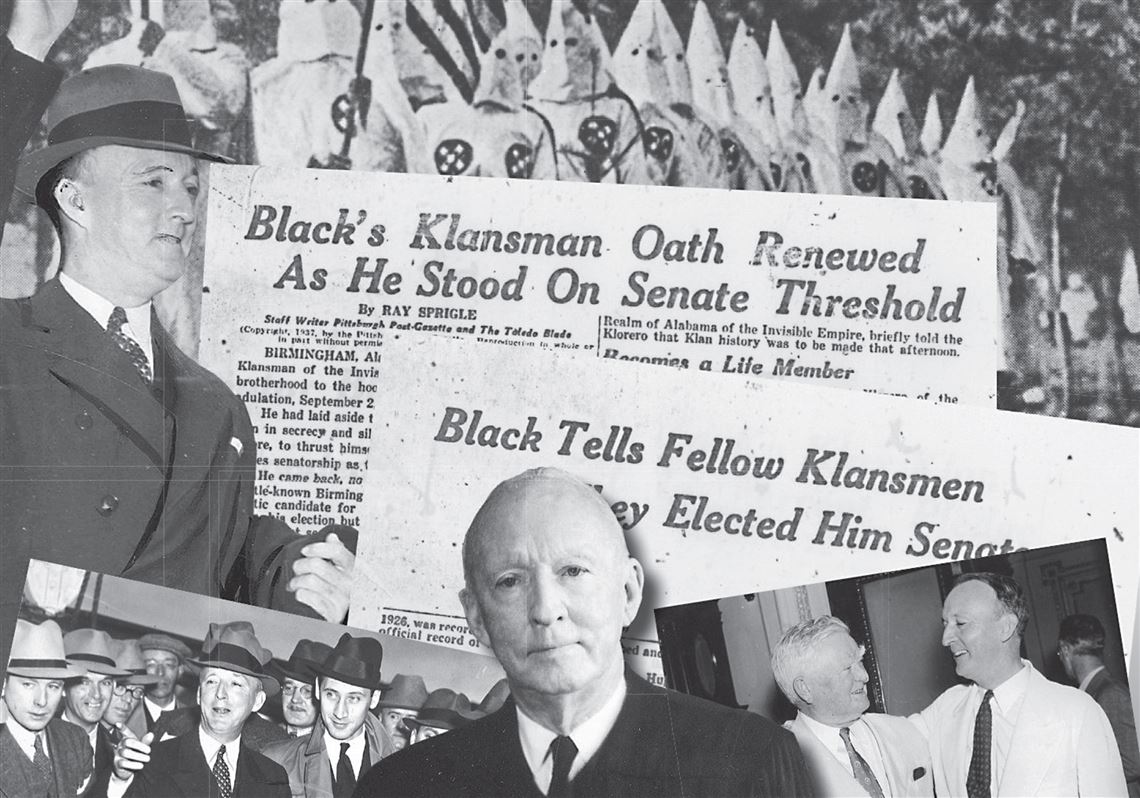

That story, actually a series of stories, began running in both papers Sept. 13, 1937, and was probably the most sensational ever written about a Supreme Court nominee.

What reporter Ray Sprigle discovered was a story that should have been more than enough to torpedo any nomination. Except that, in this case, the news came too late. Days before, the U.S. Senate voted to confirm Hugo Black, a Democratic U.S. senator from Alabama, to the Supreme Court.

What President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the senators who voted to confirm Black didn’t know — though some had suspected — was that Black had been a full-fledged member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Though it was sometimes said in later years that Black’s membership had been a brief youthful aberration or a membership on paper only, the Block newspapers showed it was anything but.

In the week-long series of articles run simultaneously in The Blade and the Post-Gazette, the newspapers showed conclusively that Black had been a dues-paying Klan member for years and had been the Klan’s “hand-picked” candidate for the U.S. Senate in Alabama in 1926, as Frank Brady would put it in “The Publisher,” his 2001 biography of the Paul Block.

Though the Great Depression was still dominating the U.S. economy, and had, in fact, deepened that year, Block, who had bought both newspapers in 1926, told his editors to spare no expense to track down the story. His reason for doing so was simple, his son, Paul Block Jr., said many years later. “Father just wanted to go after Black because of the Klan. He just abhorred it.”

The unusual route to a scoop

The story of how the newspapers got the scoop sounds like something out of a Front Page-era movie about the press.

It came about because of a publisher’s love of cards and a reporter’s knowledge of chickens.

Paul Block, on vacation in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., was a passionate bridge player who was sitting through a seemingly endless series of games one night in August 1937.

Herbert Bayard Swope, a former editor of the New York World, was somewhat of an expert on the Ku Klux Klan and had supervised a Pulitzer Prize-winning series on the “invisible empire” in 1921.

Suddenly, between games, Swope asked Block if he knew that Hugo Black was a member of the Klan.

“Block, though taken aback, knew a news story when he heard one,” Frank Brady wrote. Within minutes, the publisher was back in his hotel room calling the city desk of the Post-Gazette.

By the time he reached the night editor, Joe Shuman, it was after midnight, but that didn’t matter: This was big news — if they could prove it. And both knew there was only one man for the job: Ray Sprigle, one of the nation’s best investigative reporters.

Block told Shuman to wake up Sprigle, who lived on a 103-acre chicken farm, and get him on the next plane to Alabama. Four hours later, Sprigle was in the air. Four days later, he had the story nailed down and had found proof that the president had nominated a life member of the Ku Klux Klan to the Supreme Court.

Then and now

Today, such a revelation certainly would kill any chance of confirmation. But nominees back then did not undergo anything like the rigorous vetting process they do today.

Roosevelt sent the nomination to the Senate Aug. 12. Five days later, on Aug. 17, the Senate, eager to recess for the summer and leave the sweltering heat of Washington, confirmed Black’s nomination, 63-16, with an astonishing 17 senators not voting.

Some of those abstaining felt that Black, who had been a vigorous supporter of the New Deal, was too far left. And he had, indeed, supported FDR’s disastrous attempt to “pack” the court by adding more justices.

Others abstaining were Roman Catholics worried about the persistent rumors that Black had been a Klansman, according to Roger Newman, author of “Hugo Black,” the definitive biography of the justice. But many fears were neutralized by Sen. William Borah, a Republican and the senior member of the Senate Judiciary Committee who was known as the “Lion of Idaho.”

“There has never been one iota of evidence that Sen. Black was a member of the Klan … and there is no evidence to the effect that he is,” Borah’s famous voice intoned. “What is there to examine?”

As it turned out … a lot.

The chicken connection

Reporters had, in fact, gone to Alabama to try to ferret out hard evidence of Black’s Klan membership, but found nothing but speculation. That was because the hard evidence was locked in an iron safe owned by James Esdale, a disbarred lawyer in Birmingham.

Sprigle, a reporter’s reporter, nosed out that Esdale had been a grand dragon of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, when the Klan was at its most dangerous zenith, with millions of members in the North as well as the South.

Sprigle went to see him, and learned that the former grand dragon had a grudge against Black. Esdale had lost his license to practice law that year for illegally soliciting business. He felt that Black should have done something to help him, such as give him a job, probably because the Klan had helped Black get elected to the Senate in 1926. The fact is, Black hadn’t given any Klan members patronage positions after he got to the Senate.

Sprigle had learned all this, but he didn’t press Esdale for evidence of Black’s Klan membership right away after he took a cab to the old Klansman’s home. They drank, smoked and chewed tobacco — and talked about chickens.

Esdale’s son wanted to raise chickens, and Esdale was going to set his son up with a flock of Leghorns. “Don’t do that,” the reporter told him. Leghorns, he said, laid a lot of eggs, but weren’t good eating.

“Have your boy raise Wyandottes,” he advised. Wyandottes were large birds with a lot of tasty meat, and there were fine egg-layers as well. The former grand dragon was grateful.

Late that night, he phoned Sprigle and asked him to come to his office the next day. The reporter showed up with chewing tobacco for his new “friend,” and Esdale opened his safe.

Within seconds, Sprigle had everything he needed, from records of Black’s application for Klan membership, to his dues card, to a cynical “resignation letter” written when he was running for the Senate. He later was readmitted and made a life member.

The documentation was astounding. While Esdale clearly wanted revenge against Black, he also was in bad financial straits, likely because he could no longer practice law.

Sprigle later told Paul Block Jr. that he had paid for the documents — and then sent the Alabamian and his family on an all-expenses-paid vacation to New York City with the understanding that Esdale would arrive with two suitcases full of Klan documents.

Within a few days, on Sept. 13, 1937, the Post-Gazette and the Toledo Blade began publishing their explosive front-page series on Black’s Klan membership in vivid, purple prose.

“Hugo Lafayette Black, associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, is a member of the hooded brotherhood that for 10 long years ruled the Southland with lash and noose and torch.”

The justice’s biographer, Roger Newman, noted, “Most significant, Sprigle was claiming that Black was still a member of the Klan.”

The president was stunned. “It knocked me out of the damn chair,” Roosevelt told a confidant. The new justice was vacationing in Europe and ducked the press.

Back in Washington, there were loud calls for Black’s resignation or impeachment. FDR sent word to Black that he thought he owed the nation an explanation, and the new justice responded on Oct. 1 with a nationwide radio address in which he said “before becoming a senator, I dropped the Klan. I resigned and never rejoined. I have had nothing to do with it since that time.”

That seemed to satisfy many people, and the controversy faded. Three days later, Black hired a Jewish law clerk and a black messenger; he already had a Roman Catholic secretary.

Indeed, whatever the truth about the duration of his membership in the Klan, Black served 34 years on the court and would come to be seen as one of the most liberal judges in history; he pushed, for example, for faster school desegregation than the court actually mandated.

Whether any of this was in reaction to his having been exposed as a former Klan member is not known; he later told people his Klan membership was only a cynical move to get votes.

What is clear is that Paul Block, who owned the newspapers, was himself a Jewish immigrant from Germany and fiercely opposed to racism in any form — and he said so in a rare, signed editorial that ran in both of his newspapers the day that the Hugo Black series began.

“The bigotry and intolerance of a Klansman have no place on the highest judicial tribunal of our land … only a short time ago, inflamed race prejudice in a Southern town, Scottsboro (Alabama) was about to railroad a group of colored boys, some held on flimsy evidence, to summary death. The Supreme Court intervened and set aside the verdict of the state — holding the trial hadn’t been fair because colored people had been barred from serving on the jury. Would a Klansman have taken the same firm stand for equal civil rights for the colored race?”

Fortunately, Black didn’t behave like a Klansman on the court. Paul Block, whose energy made the coverage happen, didn’t live long enough to see Black evolve; he died of cancer in 1941.

Sprigle won the Pulitzer Prize for exposing Hugo Black’s Klan membership and continued to have a distinguished reporting career until his death in a car accident in 1957.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Toledo Blade still are owned by Block Communications Inc., at a time when family ownership of newspapers is increasingly rare, and both papers continue to do independent and enterprising journalism today.

Jack Lessenberry is a former national editor of The Blade of Toledo, Ohio, which is owned by the Post-Gazette’s parent company, Block Communications Inc.

First Published: October 14, 2018, 12:00 p.m.