Old actors never die. They prefer to let their really old film characters die for them.

Movie history is filled with the swan songs of late-life stars, running the geriatric gamut from poignant to pathetic, iconic to ironic. They often come in duets -- Katharine Hepburn and Henry Fonda's "On Golden Pond" comes to mind, or Kate and Spencer Tracy in "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner?" Sometimes you get a trio, as in "The Whales of August," somewhat overloaded with Bette Davis, Lillian Gish and Ann Sothern. For the male animal, such tours de force frequently consist of grumpy old men in comic pairs (Lemmon and Matthau) or a grizzled, cantankerous curmudgeon, playing out his last lonely chess match with the Reaper.

They don't get grumpier or more grizzled than 78-year-old Clint Eastwood in "Gran Torino." He plays aging Korean War vet Walt Kowalski, a not-so-distant cousin of Stanley -- and not so gracefully aging. He is a bigot in general but particularly abusive and hateful toward his Asian neighbors -- until they get in trouble with a noxious gang. That requires him to shift into AARP vigilante mode and gradually reveal his heart of grumpy gold.

In Nick Schenk's predictable script, everybody but Clint is a cardboard character (Walt is pressed fiberboard). The director-star indulges himself to the extent of including a final theme song, crooned or, rather, growled in his own hoarse voice. But Eastwood's patented loner -- the man who can learn and change, even in his dotage -- is a crowd-pleasing performance, virtually critic-proof.

For that matter, most of his portrayals have been critic-proof over the years. A child of the Depression, the San Francisco native worked as a lumberjack and gas-station attendant and did a four-year stint in the Army Special Services before becoming a Universal bit player ("Francis in the Navy") and then landing a nice seven-year run (1959-66) as Rowdy Yates on TV's "Rawhide."

From there, he graduated -- some might say flunked -- to the legendary spaghetti Westerns in Italy, playing "the man with no name" in Sergio Leone's "Fistful of Dollars" (1964), "For a Few Dollars More" (1966) and "The Good, the Bad & the Ugly" (1967), all wildly successful at the box office. A partnership with Don Siegel led him from "Coogan's Bluff" (1968) and "Two Mules for Sister Sara" (1969) to the immortal title role of "Dirty Harry" (1971) and its sequels -- that violent vigilante hero and significant figure in the American culture war, loathed as "fascist" by the left and loved as "a tortured vision of conservative ideals at the breaking point" by the right.

One of his best performances came against type in "Play Misty for Me" (1971), the first film he directed, in which he cleverly undermined his own Alpha-macho image. Others of note from those days: "High Plains Drifter" (1973), the eccentric "The Outlaw Josey Wales" (1976) and the charmingly funny "Bronco Billy" (1980) -- Eastwood being a much better comedian than most critics gave him credit for.

He acted in nine of the 10 pix he made between 1980 and 1990, excluding the excellent Charlie Parker biopic "Bird" (1988). The best, and least appreciated, of those was "White Hunter, Black Heart" (1990), based on Peter Viertel's novel about John Huston and the making of "African Queen."

Years ago, Viertel was asked about Eastwood's wooden presence as a straight-dramatic actor. "He's no Orson Welles," said Viertel, "but he has other virtues." Indeed, Eastwood is a kind of latter-day laconic Gary Cooper. But in the end, there was less to Cooper than met the eye, whereas there's more to Clint. He would become a superb businessman-producer of his own Malpaso Productions -- in film historian David Thomson's words, "a golden goose for the studios lucky enough to have his films, a model of managerial economy and of fruitful independence."

Eastwood's critical and commercial apotheosis was "Unforgiven" (1992), the dark, elegiac, revisionist Western that won him the best picture and director Oscars. Since then, "Bridges of Madison County" (1995) showed yet again that he has his finger on the sentimental pulse of the public, while his two staggering Iwo Jima films proved his command of the epic.

So much for career rundown. Here's the quick romantic rundown: Maggie Johnson (30 years, two kids), Sondra Locke (co-star of six films, palimony suit), Jacelyn Reeves (flight attendant, two kids, no marriage), Frances Fisher (one kid, no marriage), Dina Ruiz (TV reporter, 35 years younger, one kid). Unlike Sarah Palin, Clint gets a "bye" for out-of-wedlock family affairs, such is his high international regard.

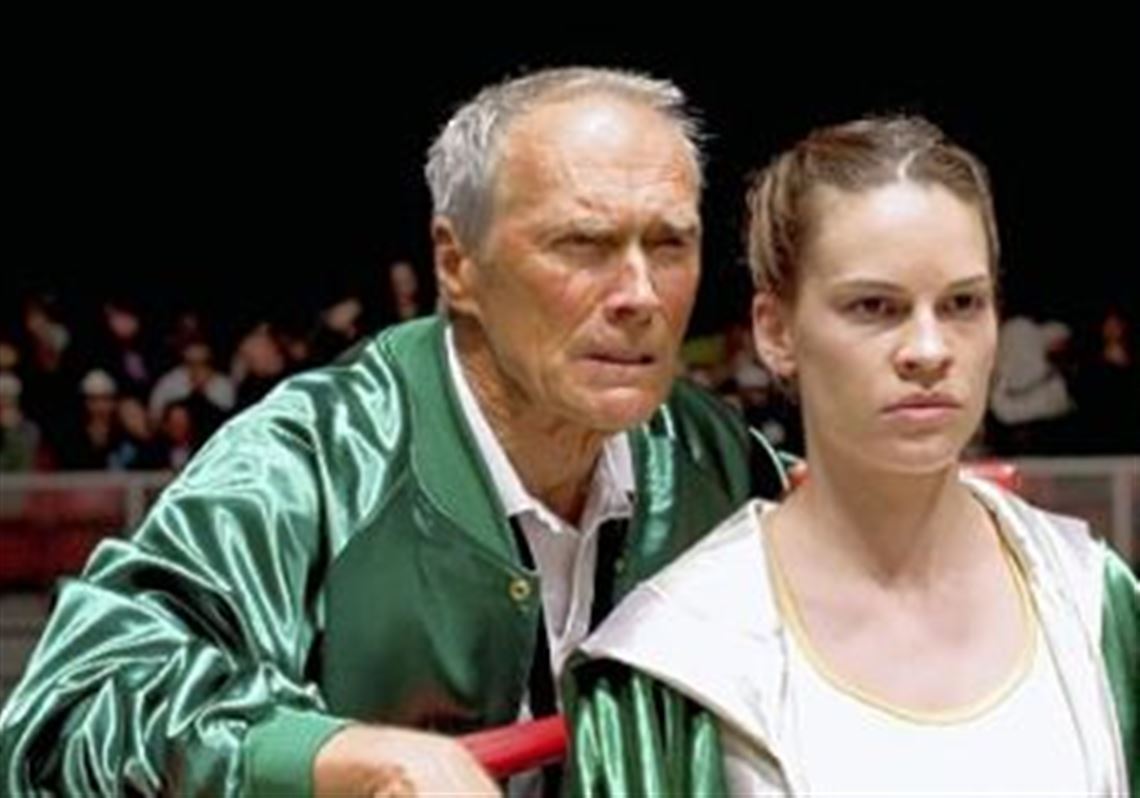

His crews call him "Zen Daddy" on the set. As director and actor alike, he seems to be aware of his own limitations and to be beloved, no matter what he does, short of a Pee-wee Herman impersonation. "Mystic River" (2003) brought Oscars to Sean Penn and Tim Robbins. "Million Dollar Baby" did the same for Hilary Swank. "Gran Torino" might do the same for Eastwood this year.

Will it be the old cowboy's final acting role? Don't bet on it. He has already had almost as many valedictory performances as Judy Garland. And he's got longevity in the genes. His mother, Ruth, just passed away two years ago at the age of 97. In a recent interview with Gail Sheehy, Eastwood recalled one of his last exchanges with mom:

"I said, 'C'mon, Ruth, we're going to make 100!' But she said, 'No, I've been here long enough.' ... When the time comes that you don't enjoy it, that's a good time to give it up."

Judging by "Gran Torino," he's still very much enjoying it.

First Published: January 9, 2009, 10:00 a.m.