Ging Cristobal posed a series of questions to a roomful of 50 people in Quezon City, Philippines, during a recent training session.

She asked about people's gender identities including, “How many here were born male and identify as female?” to which a transgender woman raised her hand and was met with a murmur of applause in the village hall.

By speaking in a mix of Tagalog and English, known as “Taglish,” and layering them in a manner of deductive reasoning, Ms. Cristobal explained the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE). These concepts are not always easy to understand, as some terms like “transgender” and “cisgender” do not have direct translations in the Filipino language. (Cisgender means someone whose gender identity corresponds with the sex they were identified with at birth.)

Ms. Cristobal, OutRight International’s project officer for Asia, is working on building an LGBTI-friendly network — the "I" in LGBTI stands for "intersex" — starting at the very basic, grass-roots level of the village. At the recent meeting, her audience members were village council officers who serve as guardians and executors of Quezon City's Gender-Fair Ordinance.

About 15 other cities around the country have passed their own anti-discrimination ordinances but none have quite followed through with the vigor and determination as Quezon City, a bustling metropolis about 9 miles from the Philippine capital of Manila.

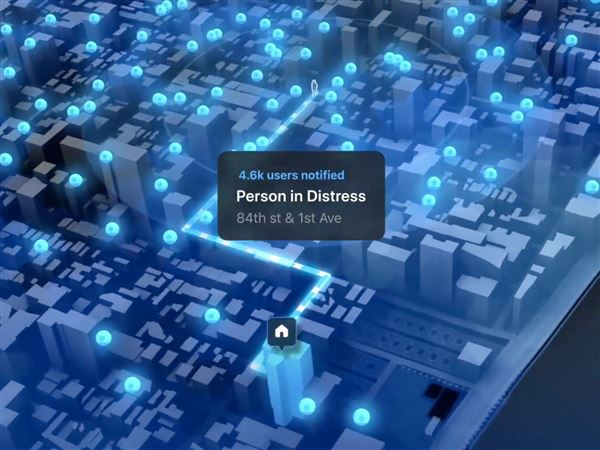

Ms. Cristobal has already conducted SOGIE workshops in almost half of Quezon City’s 142 villages. The training includes educating village officers on the different ways that violence and discrimination may be inflicted on LGBTI individuals, as well as the redress mechanisms that are available to them. Quezon City has also set in motion a Pride Council to oversee the implementation of LGBTI services, including a related hotline.

“I’ve always looked at LGBTI rights from a human rights perspective,” said Quezon City Vice Mayor Joy Belmonte, who made an appearance during the SOGIE orientation to plaster rainbow decals on the village hall's windows. The sticker certifies it as an LGBTI-friendly space where any of the officers trained by Ms. Cristobal will be ready to extend assistance with sensitivity and respect.

Afterward, Ms. Belmonte posted a rainbow sticker on tricycles, motorized carriages that are a popular mode of transportation in the Philippines. Ms. Belmonte explained to drivers that the sticker signifies their agreement to bring any LGBTI person who needs help to the nearest village hall also marked with the colorful visual.

'Confused' state

Initiatives like this make it easy to see why the Philippines has a reputation for being a gay-friendly country. Pockets of various cities — including Quezon City — are lit up by gay bars, and gay beauty pageants are enjoyed in almost every village across the nation. Hints of gender equality are also present in national legislation. There is the Ladlad political party whose platform is gender rights and equality. Two women have served as heads of state — and both came to power by overthrowing a sitting male president. Last year, the country elected its first transgender congresswoman.

But looking deeper, there is little acceptance in places where it matters the most. A 2012 study of 59 transgender, lesbian and bisexual women conducted by the advocacy group, Rainbow Rights Philippines, said that participants felt a “significant level of invisibility and devaluation.”

The discrimination and stigmatization people described ran across three groups: family, religious institutions and law enforcement.

“In terms of LGBTI rights, we are a bit of a confusing case. The sector is fairly well-represented. ... At the same time, we have high rates of violence against LGBTI individuals,” said Sharmila Parmanand, a Filipina who is a gender studies PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge.

Ms. Parmanand highlights the fact that LGBTI youth are bullied and discriminated against by peers and teachers in the country’s massive network of religious schools. Sodomy and homosexuality are not criminalized, but there is little legal protection available as there is no national law that prohibits discrimination on account of gender identity, orientation or expression.

Gender-fair laws, if any, are instituted at the city level, as in the case of Quezon City.

First Published: April 24, 2018, 1:15 p.m.