The Hubble Space Telescope usually peers deep into space, revealing sights unseen and giving cosmologists and astrophysicists insights into the Big Bang and the evolution of the universe.

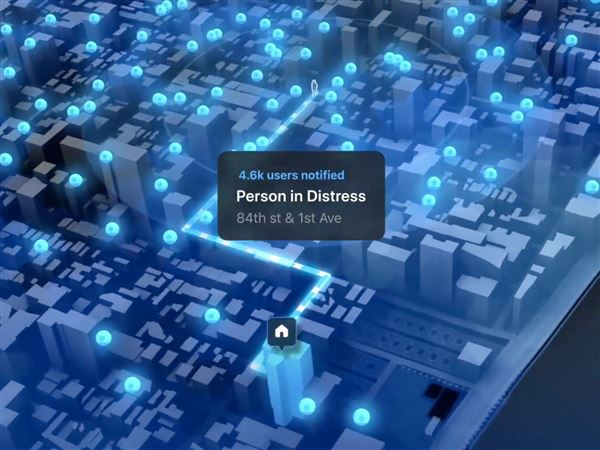

The Hubble Space Telescope's Advanced Camera for Surveys snapped this close-up view of the Aristarchus crater on the moon Aug. 21. The crater is a promising site for an ore from which oxygen could be extracted.

Click photo for larger image.

Graphic: A canyon and a crater

Graphic: A canyon and a crater

For three days in August, however, Hubble fell into the hands of geologists, who focused the school bus-sized instrument on the moon.

Using the mighty Hubble to study the moon, the first object that a kid with a new telescope is likely to spy, might seem like overkill. But Jim Garvin, chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., says the observations during August's full moon were nothing less than "a masterpiece, as yet unfinished."

Hubble produced the first high-resolution images of the moon in ultraviolet light -- a frequency that renowned University of Pittsburgh planetary scientist Bruce Hapke says should prove valuable in the search for oxygen-bearing ore on the moon.

In particular, spectroscopic analysis of the ultraviolet light reflected from the moon's surface could tell scientists where the highest concentrations of a mineral called ilmenite can be found on the moon.

Scientists suspect that ilmenite, composed of iron, titanium and oxygen, might provide an easily accessible source of breathable oxygen for future explorers and inhabitants of the moon. The mineral is found in basaltic rock; the process of extracting oxygen from the ilmenite in this rock can also produce water, which in turn can be a source of hydrogen for rocket fuel.

Dr. Garvin said these studies are useful both for lunar science and for determining the best landing sites for future human exploration, now slated to commence in 2018.

Mark Robinson, a planetary scientist at Northwestern University and a co-investigator for Hubble's lunar observations, said the Apollo landings and the 1994 Clementine and 1998 Lunar Prospector orbital missions clearly established the presence of ilmenite and provided a good idea of its distribution on the moon.

But if ilmenite should prove useful for future human missions, not just any ilmenite will do. Extracting oxygen will depend on finding rock with high concentrations of ilmenite, he explained, and the ultraviolet spectroscopy should help scientists determine where the richest ilmenite ore can be found.

Using the Hubble to image the moon was not as easy as it sounds; it is actually one of the most technically challenging observations to be made with the space telescope, said Jennifer Wiseman, Hubble program scientist.

The Hubble is moving five miles per second, which is not a big deal when it is looking millions of light years into deep space. But focusing it on a moving object only 250,000 miles away was another matter. Dr. Garvin likened it to a blind quarterback completing a 50-yard pass to a receiver who can't see the quarterback.

For this study, the researchers focused Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys on three sites -- the landing sites for Apollo 15 and 17 and the giant Aristarchus impact crater and adjacent Schroter's Valley.

Aristarchus is "one of the most geologically breathtaking places on the moon," Dr. Garvin said. Twice as deep as the Grand Canyon and measuring 26 miles across, Aristarchus was a potential landing site for Apollo 18 and 19 before they were cancelled.

"It is a very diverse area," said Dr. Hapke, who is among the co-investigators. Much like a fresh road cut, which reveals rock strata to eager geologists, Aristarchus is one of a handful of relatively young craters that allow geologists to peer into the moon's past. It includes a large hunk of ancient lunar crust, which is buried elsewhere on the satellite, and is in an area of volcanic activity and lava flows. The crater and Schroter's Valley also are promising sites for ilmenite ore.

The Apollo sites, by contrast, are sources of comparison for the investigators as they try to interpret the Aristarchus images. More than 1,000 pounds of moon rocks and soil were gathered by Apollo astronauts. No place was more extensively sampled than the Apollo 17 site, where geologist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt cruised 25 miles on the lunar rover to collect soil and rocks.

Because those Apollo sites are so well characterized, the scientists can use them as "ground truth" to interpret the Hubble images and in turn apply those lessons to analyzing the Aristarchus images.

"We had known from some previous laboratory work that I had done that there was spectrum information observable in the ultraviolet," Dr. Hapke said. In spectroscopy, scientists can often determine the presence of elements based on the frequencies of light that they reflect. "We can see a great deal of diversity in the ultraviolet. Now, we're trying to figure out what it all means."

Figuring out how to interpret the UV spectroscopic data is important as scientists prepare for the 2008 launch of NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, said Dr. Robinson, that mission's chief scientist. The orbiter will include an ultraviolet spectrometer and will spend a year circling the moon while it develops detailed maps of the surface.

In addition to looking for ilmenite, the orbiter will be taking a close look at the moon's polar regions, where scientists suspect that large quantities of water ice might be found inside craters. Water would be another important resource that astronauts could exploit.

The more resources, such as air, water and components for rocket fuel, that astronauts can find on the moon, the less that needs to be launched from the Earth. Exploiting the moon's resources could reduce exploration costs and extend the time astronauts spend there.

Lots of materials on the moon contain oxygen, Dr. Garvin said, but not many of them give up their oxygen as easily as ilmenite. Researchers are now studying how best to unlock ilmenite's oxygen -- heating the ore or applying electric current are two potential methods.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will generate "a Niagara Falls of data," Dr. Robinson said, so figuring out now how to interpret the UV data will provide an important headstart to that mission.

"We weren't sure what we were going to get," prior to the Hubble images, Dr. Hapke said, but the initial results suggests that the UV spectrum will be as useful as hoped. But completing the analysis, he warned, could take some time.

"We'll probably be doing it for a couple years."

First Published: October 24, 2005, 4:00 a.m.