A clinical study conducted in South America by local researchers has found that injections of bone marrow cells can pump up a failing heart.

Patients who received stem cells during bypass surgery had hearts that pumped blood more effectively months later than those of patients who got surgery but no cells.

Stem cells are precursor cells that generate specialized cells. The stem cells in the bone marrow normally would produce blood cells, but in this trial, the researchers suspect, they may produce new blood vessels.

Though the study included just 20 participants, it is the first to compare what happens to heart failure patients who get stem cells with those who don't receive the cells.

"This is definitely a move forward," said Dr. Samuel Dudley, a cardiologist at Emory University in Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. "This is definitely needed in the field."

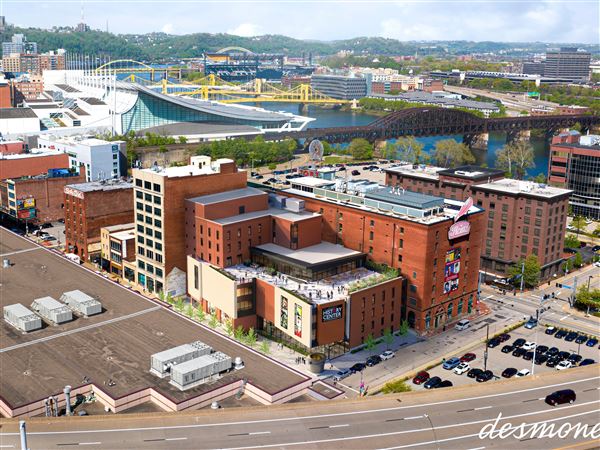

Dr. Amit Patel of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and collaborators from Pitt, Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas and the cardiovascular surgery department of the Benetti Foundation in Rosario, Argentina, conducted the trial at multiple centers in South America.

Patel presented their findings yesterday in Toronto, Canada, at a meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

The study participants had heart failure because insufficient oxygen was getting to the muscle, which can be caused by coronary artery disease. The severity of the condition left them breathless even while resting or minimally active.

The patients had ejection fractions ---- a measure of how much blood is pumped out of the heart with each beat ---- of less than 35 percent. A normal ejection fraction is at least 55 percent.

All the patients underwent bypass surgery to try to improve blood flow to the heart muscle. But half of them were randomly picked to have stem cells injected into 25 or 30 damaged areas of their hearts. The cells were isolated from the patients' own bone marrow.

The researchers measured ejection fraction again one, three and six months later. After one month, both groups improved. The patients who received bypass alone had an average ejection fraction of 36.4 percent, up from a preoperative value of 30.7 percent. The stem cell patients went to 42.1 percent from 29.4 percent.

"If you're in heart failure and you receive bypass surgery, you should have some improvement because you're getting more blood flow to your heart," Patel explained. "Then it stabilizes."

That's because the surgery doesn't make the heart pump better, he said. The bypass-only group had ejection fractions of 36.5 percent at three months and 37.2 percent at six months.

But the stem cell group had ejection fraction improvements at the next reassessments. The group average at three months was 45.5 percent and at six months it was 46.1 percent.

One of the stem cell patients told Patel that he was able to walk six blocks, a level of exercise he hadn't achieved in years.

"Their clinical improvements have been very dramatic," he said. The bypass-only group also feels better, but have more residual heart failure symptoms than their counterparts, Patel added.

The researchers also performed heart catheterizations to obtain muscle biopsies.

The tissues showed that patients who got stem cells had a greater amount of a protein marker called connexin 43. Its presence could indicate that the heart muscle cells were better able to communicate and work together.

None of the patients suffered arrythmias, neurologic problems or other serious side effects, Patel said.

Some experts, writing earlier this month in the journal Science, worried that eagerness to help cardiac patients might outpace safety concerns and the development of a sound understanding of how the cells work.

Much remains to be learned about the appropriate timing, delivery and types of cells necessary for treatment, or if stem cell therapy will prove effective over time.

Still "the implication of [the Pitt] work is tremendous," said Dr. Piero Anversa, director of the cardiovascular research institute at the New York Medical Center. "It is very encouraging and promising in terms of the therapeutic potential that bone marrow cells have."

Patel's study was conducted in South America because governing bodies were ready to move forward, not because American regulators were against the research. He is working on getting approvals to begin trials here.

"They want to do it in a controlled fashion," Patel said. "It is coming to the United States, not years from now, but probably months from now."

Meanwhile, he and his colleagues have begun delivering stem cells in a minimally invasive fashion for patients who have heart failure that cannot be treated with surgery.

Two patients were treated in Uruguay in that study, which could also include participants in Palermo, Italy, where the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center manages a transplant program.

Locally, researchers plan a study that gives stem cells to patients who are implanted with heart assist devices while they await a donor organ. After the recipient's own heart is removed after transplantation, the researchers will be able to more closely examine the effects of the stem cells.

First Published: April 26, 2004, 4:00 a.m.