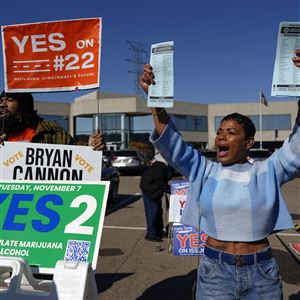

The tableau of striking teachers carrying picket signs in the Seneca Valley School District in Butler County last week is a familiar one, played out 974 times in Pennsylvania since teachers won the right to strike in 1970.

But along with the strikes has come another perennial: legislative proposals to outlaw them.

"There's typically one per session, at least," said Tim Allwein, assistant executive director for governmental and member relations of the Pennsylvania School Boards Association.

While there have been many proposals, it has been 15 years since any changes were made in the law governing teacher strikes. Although the changes -- embodied in Act 88 of 1992 -- significantly reduced the number and length of strikes, some think the act did not go far enough.

State House Republicans have introduced two bills so far this year. One, whose chief sponsor is state Rep. Bob Bastian, R-Somerset, an area where one teachers contract dispute took five years to resolve, calls for a constitutional amendment banning strikes.

The other bill, introduced by state Rep. Todd Rock, R-Franklin, would ban strikes and set a penalty for those violating the law: Teachers would forfeit two days' pay for each strike day and individuals would have to pay $5,000 for inciting a strike.

It also would set up increased public scrutiny -- including making contract proposals public -- as well as mandatory nonbinding arbitration as ways to resolve a dispute.

Among the supporters are state Rep. Daryl Metcalfe, R-Cranberry, whose district includes the Seneca Valley district, and an organization named Stop Teacher Strikes Inc., which was formed by Simon Campbell, a parent affected by an earlier strike in the Pennsbury School District in Bucks County.

According to the school boards association, 76 school districts and their teachers are still negotiating contracts that expired this year or earlier.

In Allegheny County, teachers in Duquesne and Shaler Area have taken strike authorization votes. Pittsburgh Public Schools teachers are in the midst of a mail-in strike authorization vote.

Others who have authorized strikes are teachers in the Greensburg-Salem, Southmoreland and Yough school districts in Westmoreland County and in Connellsville Area in Fayette County, according to the Pennsylvania State Education Association, the state's largest teachers union.

None of them has set a date, and it is not unusual for members to authorize a strike that never occurs.

Pennsylvania is one of 13 states permitting teacher strikes.

Before Act 88, the number of strikes in the state reached a high point of 52 in 1980-81. But after Act 88, the number has ranged from five to 17 a year, according to the school boards association.

So far this year, there have been three: Seneca Valley and Lake-Lehman in Luzerne County, both of which walked out last Monday, and Reynolds in Mercer County, which went on strike on Oct. 9.

Act 88 limits how long teachers can stay out, provides ways for third parties to examine the dispute and requires teachers to give 48-hour notice of a strike. It also halts selective strikes -- in which teachers give short notice they would be out for a day -- and guarantees students receive 180 days of instruction.

Little enthusiasm for change

Neither the school boards association nor the PSEA have come out in support of the latest proposals.

The school boards association, which pushed for Act 88, is preparing to appoint a task force to develop a position on changing the act so that a position can be adopted by its policy council next fall.

Earlier this month, the association set a legislative platform opposing mandatory binding arbitration.

"We don't have any consensus from our members to support a bill prohibiting teachers strikes," said Mr. Allwein. "We have members that support just about everything.

"There needs to be a way to deal with strikes, whether prohibiting them altogether or creating more disincentives is the answer, I guess we'll see in the next few years."

The PSEA isn't looking for any changes in Act 88 right now.

"When they're talking about an outright ban on strikes, we're not favoring any reopening of Act 88 at this time," said spokesman Wythe Keever.

PSEA delegates in May approved resolutions reaffirming the belief in the right to strike and supporting binding arbitration only when both sides mutually agree.

"Our members believe that strikes should be a legal and rare last option," said Mr. Keever. "None of our members like going on strike, but they think it's an important last resort when negotiations don't bring about a settlement."

Joe Scheuermann, president of Hempfield Area teachers union, which went on strike last fall after the board didn't approve a tentative contract, said he wishes the tools of Act 88 had worked well enough to prevent the 10-day strike.

But he believes the strike was necessary.

"Without the strike and without the fact-finding report, I don't think we would have reached a settlement," he said.

"I understand the frustration of parents who say, 'I want my children in school,' but if teachers have no right to strike, what recourse do they have when the board is being unreasonable?"

One of arguments over whether teachers should strike revolves around who loses when one occurs. Unlike strikers in the private sector, teachers typically do not lose pay during a strike.

But Mr. Keever thinks such a comparison to the private sector is unfair because the employer, the school district, doesn't lose money either.

Bruce Campbell, an attorney in public labor law for more than three decades, said he thinks the number of strikes would be "dramatically reduced" if teachers lost money during a strike. He suggested not permitting teachers to make up missed in-service days and requiring them to pay for their own health insurance during a strike.

Under Act 88, teachers can strike up to the point at which the district can still schedule 180 days of instruction by June 15. Then, both sides must submit the dispute to nonbinding arbitration.

If the arbitrator's recommendations are rejected by one or both sides, then the teachers can strike again, this time up to the point at which the district can schedule 180 days of instruction by June 30.

The result is that most strikes last only a few days or a few weeks.

Under the old law, strikes could last for months.

Help from fact-finders

Act 88 also provides some help before a strike is declared, including a state mediator and a voluntary fact-finding.

It appears to have made a difference.

From 1992 through 2006, the state Labor Relations Board appointed 543 fact-finders in contract disputes involving teachers and other school employees. Of those, 39 percent of the disputes were settled by the end of the process, including 16 percent before a fact-finding report was issued and 23 percent which mutually accepted the recommendations.

No similar figures were available for nonbinding arbitration.

The process helps even in cases where the fact-finder's report is rejected, Mr. Campbell said.

"Fact-finding tends to narrow the issues of a dispute," said Mr. Campbell, who thinks the state should order more fact-finding. "When you go before a fact-finder, it tends to make people get more realistic about their proposal. They tend to focus on the more important issues."

Two of the biggest issues at bargaining tables are salary and health care costs.

When it comes to salary, teachers and school districts sometimes give different sets of numbers, even for the same proposals.

That's because they approach them with different points of view. Some boards look at an overall percentage, including the pay increases at each step as teachers move up the salary scale. Some teachers look at the raises above and beyond those already provided at the various steps.

School districts are trying to get teachers to contribute to health care premiums, or, if they already do, to contribute more.

"Health care costs are at the core of most of the work stoppages we've seen in the last number of years," Mr. Allwein said.

First Published: October 21, 2007, 4:00 a.m.