Not many people would complain about a 60-degree day in February. But this winter’s temperature spikes could mean even earlier exposure to one of spring’s downsides: potholes.

Tech gurus can’t stop the weather conditions that cause asphalt to weaken and crack — eventually opening up gaping holes large enough to swallow a Goodyear tire or mess up a Jeep’s alignment. But armed with smartphones, algorithms and self-healing asphalt, they’re trying to make road maintenance a little more manageable.

While some are experimenting with high-tech ways to fill the pothole once it pops up — like using a 3D printer and a drone to fix a crack almost instantly or creating asphalt that will repair itself with a little extra heat — others are looking at better ways to monitor the problem that costs Americans millions annually in road and vehicle repairs.

In Pittsburgh, East Liberty-based RoadBotics already has a platform called RoadWay that uses a smartphone and machine learning to tell governments, municipalities and other stakeholders which of their roads are in bad shape or are on their way there.

This month, it is rolling out a software update meant get even deeper into the pavement. Now repair teams using its tools should be able to pinpoint the exact locations of road “distresses,” like potholes, patches and cracks. “Having this tool lets you come in with scalpel precision,” promised co-founder and president Benjamin Schmidt.

Even Tesla leader Elon Musk has said he wants his electric cars in on the pothole fixing fad. He said the autopilot feature, which makes the cars somewhat autonomous, can identify and map potholes. It’s unclear how well the system works.

The idea of using machine learning to monitor potholes and roads has been around for decades, according to Kumares Sinha, professor of civil engineering at Purdue University. Before cameras and sensors, he and his team relied on human eyes mapping every inch of the road.

For Mr. Sinha, the real pothole solution might lie in the ingredients of the road.

“How much gravel? How much sand? How much cementing material, the binding material? That makes a big difference,” he said. “All these affect construction and maintainability.

“If we could use the magic wand and have the perfect ratio for these materials, perfect construction packages, then it will last forever. But it doesn’t.”

What the next advancement will be and how quickly we get there boils down to money, Mr. Sinha said.

It can cost $1.25 million per mile to resurface a four-lane road, according to the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, a nonpartisan federation based in Washington.

Constructing a new two-lane road in an urban area can cost up to $5 million per mile, though most designated funding goes toward repairing and maintaining existing roads and bridges rather than building new ones.

Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto has committed to spending $16.9 million to pave roads this year, building on a years-long effort to make potholes a priority.

So far it has worked, according to Mr. Peduto’s director of communications Tim McNulty. The city has seen a drop in the number of pothole complaints it receives in the last three years, he said.

In January 2018, it had 1,800 complaints. The same month in 2019, it had 447. This January, it received 382. (2018 was an unusually “wet” year with a record 57.42 inches of precipitation, which could have contributed to more potholes than usual.)

Staying in the green

RoadBotics, which spun out of Carnegie Mellon University, doesn’t work with the mayor’s office, but said it is in conversations with another customer to map Pittsburgh’s roads. To date, the company has tracked about 30,000 miles of pavement in 34 states and 14 countries.

In the existing RoadBotics system — first rolled out in 2016 — a smartphone mounted to a windshield collects images and data. A software platform then uses that information and machine learning to create a detailed map of the state of each road.

The roads are rated on a scale of 1 (no or minor surface distress) to 5 (major surface damage and/or critical fatigue issues) and color coded from green (good) to red (bad.)

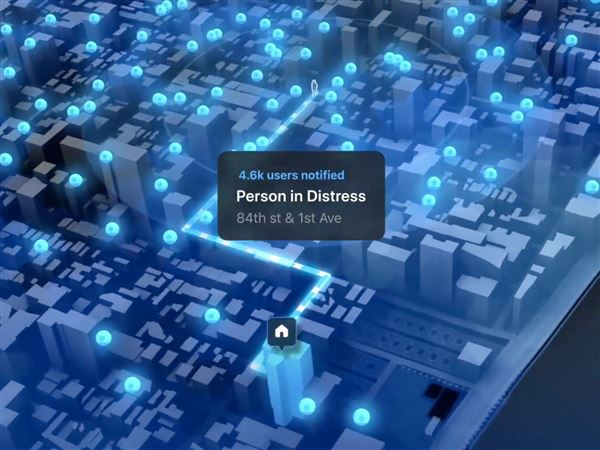

From a wide angle, the map can easily show a colorful key of the good and bad roads. With the new software, as you zoom in, it can show specific distresses marked by “road lollies,” or virtual pins. The more you zoom, the more lollies appear.

The cost of RoadBotics’ services varies, but the company typically charges about $100 per centerline — a unit of measurement that it describes as walking down the double yellow line on a road and taking in both sides of the street.

After collecting the data, RoadBotics generally takes a step back, Mr. Schmidt said.

It leaves the decision up to its customers to answer the next questions: What is their budget for fixing road infrastructure? What do they want to tackle next? Who do they want to perform the work? And, what is their plan for routinely checking on roads?

After all, a green road will probably stay in the green only for a year or two, Mr. Schmidt said.

‘A dark side’

A team in the mayor’s office in Boston has been working for about a decade on using technology to tackle that city’s pothole problem. It started with a special device that would sit in the bottom of the mayor’s car and track potholes based on the car’s movement, according to Nigel Jacob, co-chair of the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics.

The team quickly pivoted to using an iPhone instead and created a “Street Bump” app open to the public for crowdsourcing pothole complaints.

But it became clear that the public reporting was disproportionately centered in wealthy areas of the city — where lots of time and funding were already funneled.

“There is a dark side to these things,” Mr. Jacob said. There’s “generally a lack of awareness that these technologies have a human scale impact.”

Eventually, the city decided to abandon the project and expand the use of the city’s 311 system, an app already in place for crowdsourcing all sorts of city complaints, including potholes.

Street Bump is gone but potholes certainly aren’t, Mr. Jacob said.

“I think we can imagine a future where maybe there’s like self-healing pavement,” he said. “But until we get that stuff, the constant freezing and thawing of the climate is going to require a constant focus on these kinds of issues.”

Lauren Rosenblatt: lrosenblatt@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1565.

First Published: February 19, 2020, 1:00 p.m.