There’s a strange looking creature at the center of the work space in Bloomfield. It resembles a monkey — all long arms and short legs, hunched over at times, squat — but it’s metallic with red junctions and has wheels where the feet should be.

The creature is a simple robot built out of actuators designed by a Carnegie Mellon University spinoff called Hebi Robotics. Actuators are the “movers” that control a mechanism or a system, usually through an electric current or pneumatic or hydraulic pressure.

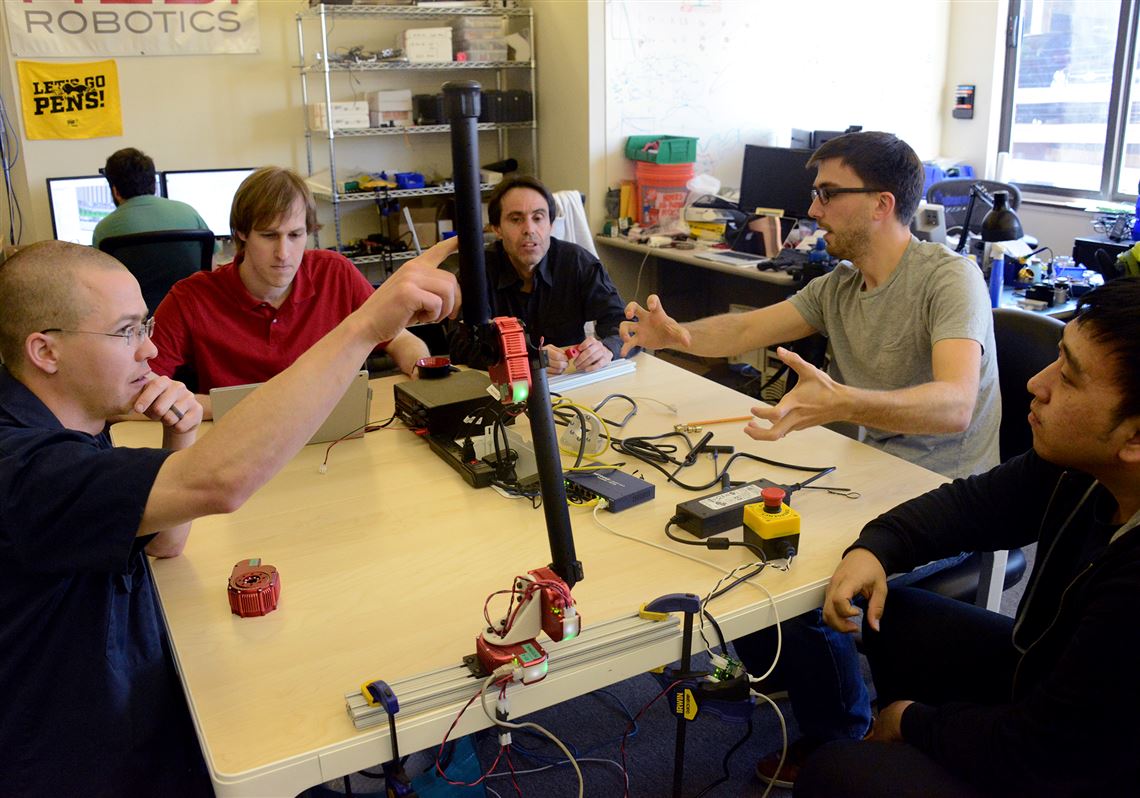

Hebi’s team of eight roboticists endearingly refer to the simple prototype as “Igor” — an apt enough name for a robot that sometimes loses its balance while zipping around the room picking up objects.

But that clumsiness is not an indicator of faulty technology. Igor is more of a platform than a product.

The robot is a showpiece for the real stars — the chunky red joints where his elbows should be. Those $3,000 actuators are the robotic building blocks that Hebi has been selling since spring 2016.

“Some companies just want one to try to be sure it fits with their design and oftentimes they come back and purchase more,” said Bob Raida, COO at Hebi. “The largest order we’ve seen is over 100 ... we have a backlog right now due to that order.”

Hebi’s production runs are small. Large orders are broken into smaller batches since the team of eight assembles each actuator by hand. Mr. Raida said the company has sold a few hundred in the past few months alone.

“We want these to be as easy to use as a Lego,” said Howie Choset, a CMU robotics professor and one of Hebi’s founders.

The joints, officially called X-Series actuators, allow engineers and researchers to expedite the innovation process, quickly configuring robots from functional units rather than starting from scratch.

The X-Series actuators were borne out of Mr. Choset’s research in snake robots at CMU. Snake robots, which are flexible like the animal, can be used to take robots into precarious spaces that are otherwise hard to reach, such as the site of a nuclear explosion or war zones where rescue missions take place.

“Hebi” is Japanese for snake, Mr. Choset said, just a few weeks after bringing one of his snake robots onto The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon in April.

The company’s entrance to the robotics manufacturing sphere is significant not only because its operation can quicken the pace of innovation, but because there’s also an immense market to capture.

In May, the Ann Arbor, Mich.-based Robotic Industries Association said robot orders and shipments had achieved record levels during the first quarter of 2017. In North America, 9,773 robots were ordered, a 32 percent growth in units from the same period in 2016. Those robots were valued at approximately $516 million.

Hebi fills some of those orders.

Mr. Raida said the company has a couple dozen customers around the globe, with most involved in lab-based research or prototyping for research and development units.

He doubts that more than three of Hebi’s customers are working on anything even remotely related.

They run the gamut from walking and traditional robots to educational uses to the downright unusual. One individual used the modules and accompanying aluminum tubing to create a “self-driving car” by attaching the robot he built out of Hebi actuators, programmed with his own software, to his steering wheel.

In industrial settings, Hebi modules can help customize production, according to Dave Rollinson, a co-founder of Hebi who holds a Ph.D. in robotics from CMU.

“A big problem in manufacturing we want to solve is what a company needs three months down the line,” he said. A company that uses robots in production but has discovered a better way to run its processes can now reconfigure existing robots, rather than scrap the whole thing and start anew.

That’s an issue in academia as well, Mr. Rollinson said, noting that CMU has a psuedo-cemetery of old robot parts in various rooms — leftovers from past research.

While he and the other cofounders of Hebi still worked at CMU in the biorobotics lab, they couldn’t focus on a solution at the same time; it took all of their collective energy to eventually spin off in 2014, honing in on manufacturing and leaving behind research.

When the team decided to spin off, they received initial seed funding from Innovation Works, and have collected between $100,000 and $150,000 to date, said Larry Weidman, executive in residence at Innovation Works. Hebi also received funding from a strategic partner and the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Since then, one of Hebi’s best-known customers has been NASA, which used the actuators in creating prototypes for its “Super Ball Bot,” a round platform used to operate on the surface of a planet. The prototype is created with long rods that rely on continuous tension to stay straight. It’s named after the children’s toy, “Skwish,” which is essentially a ball of tension rods in primary colors.

Super Ball Bot, still in development, could be the next space exploration vehicle because of its relative low cost and sturdiness.

Mr. Weidman recalled a time when the Hebi team showed him a robot and he said, in an offhand manner, that it would be interesting if the team could reconfigure the robot to perform a different function.

An hour later, the team emailed him a video of a new robot. The same components had been quickly reassembled to perform a new task.

“I think this has the potential to create a market where it didn’t exist before,” said Mr. Weidman, who also sits on Hebi’s board. “There were markets in the past for robotic arms and large scale monolithic robots who were programmed to do one thing, but this approach adds flexibility.”

Courtney Linder: clinder@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1707. Twitter: @LinderPG

First Published: July 20, 2017, 11:00 a.m.