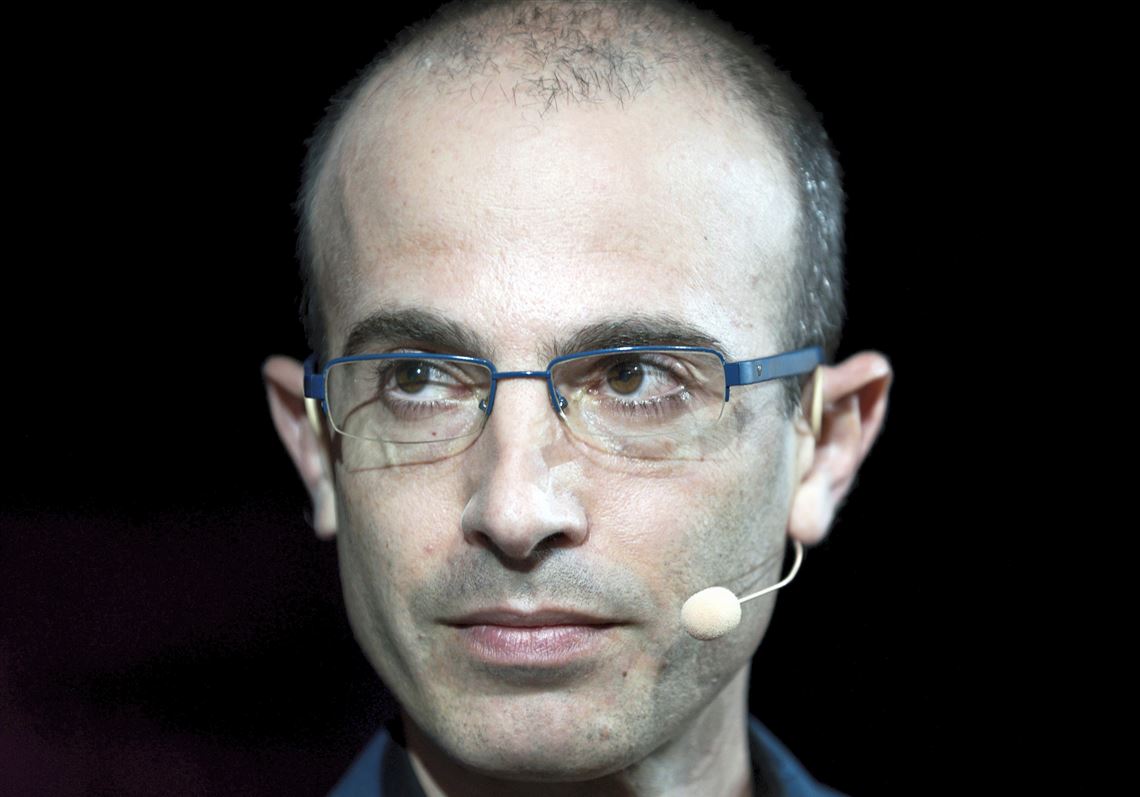

I might get lucky and die before Yuval Noah Harari’s dark predictions come true.

That’s what I found myself thinking while reading Mr. Harari’s “21 Lessons for the 21st Century.” The Jerusalem-based historian’s third book begins with a bracing look at trends in artificial intelligence and biotechnology that — unchecked by Earth’s reeling democracies and surging autocracies — could change the nature of humanity as early as 2050.

If you’re reasonably comfortable with a world in which people have some modicum of control over their lives, Mr. Harari’s book will scare you.

The science fiction vision in which technology turns from a tool to a tyrant isn’t far off, he convincingly argues. “When the biotech revolution merges with the information revolution,” he writes, “it will produce Big Data algorithms that can monitor and understand my feelings much better than I can, and then authority will probably shift from humans to computers.”

And that’s not the worst of it.

Spiegel & Grau ($28).

Mr. Harari looked backward in his first book, “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” and deep into a theoretical future in his second, “Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow.”

Now he’s bridging the gap, ruminating on this century, in which he sees “an unprecedented existential crisis” brought on by the confluence of uncontrolled technology, climate change and the threat of nuclear war.

“The decisions we will make in the next few decades will shape the future of life itself, and we can make these decisions based only on our present worldview,” he writes. “If this generation lacks a comprehensible view of the cosmos, the future of life will be decided at random.”

Oh, come on! Today we have nearly full employment and seemingly infinite streaming video options. All’s good, right?

Perhaps not. Mr. Harari reminds us that Google, Facebook and Amazon already track much of what we do and think. Throw in sensors that can monitor our bodies in increasing detail, and you get a real game-changer.

“For once somebody (whether in Beijing or San Francisco) gains the technological ability to hack and manipulate the human heart, democratic politics will mutate into an emotional puppet show,” he writes.

Or, as he puts it later: “Democracy in its current form cannot survive the merger of biotech and infotech. Either democracy will successfully reinvent itself in a radically new form or humans will come to live in ‘digital dictatorships.’”

Throw in automation, and we might be both easily controlled and largely useless. Freed by robots from toil, workers will lose the modest economic and political leverage they now have, Mr. Harari warns, heralding the emergence of “a new useless class.”

Those who control the data and can afford the fruits of the biotech revolution, meanwhile, will thrive. “By 2100, the richest 1 percent might own not merely most of the world’s wealth, but also most of the world’s beauty, creativity, and health,” he writes, postulating about the potential division of humanity into two distinct species.

Huh. In 2100? I’ll almost certainly be dead by then.

Most alarmist books eventually quench the reader’s panic with a sprinkle of hope. Mr. Harari’s, not so much. (Even the lesson on meditation is woven through with anxiety).

“If we want to prevent the concentration of all wealth and power in the hands of a small elite, the key is to regulate the ownership of data,” he writes.

That’s a glimmer. But he adds that information is notoriously hard to control, and he doesn’t suggest a framework, instead calling on “our lawyers, politicians, philosophers, and even poets” to figure it out.

He also notes that we are a species that has always rallied most readily around myths and lies, and which finds itself decreasingly able to comprehend the big picture — or even the little picture.

“Since I depend for my existence on a mind-boggling network of economic and political ties, and since global causal connections are so tangled, I find it difficult to answer even the simplest questions, such as where my lunch comes from, who made the shoes I am wearing, and what my pension fund is doing with my money,” he writes.

Enlightened political leadership has led us clear of dystopias before. But the Western, democratic ideology that seemed transcendent from 1945 through 2016 “is losing credibility exactly when the twin revolutions in information technology and biotechnology confront us with the biggest challenges our species has ever encountered,” Mr. Harari writes.

If you’ve seen anything credible and visionary out of Washington, D.C., lately, please let me know. I could use some good news.

But I don’t regret taking Mr. Harari’s “21 Lessons.” We need to know what we’re up against.

Rich Lord: rlord@post-gazette.com.

First Published: October 6, 2018, 4:00 a.m.